Analyze the data supply chain to detect overfetching

As a developer, you might think you're the one building the site, but it's the browser that does that particular job.

Every time a user visits your site, their browser and your server work together to assemble the webpage out of the HTML, CSS, and Javascript. If you have ten thousand users, that means assembling ten thousand webpages.

Your role is more like building a factory that creates websites, with the servers, databases, and browsers acting as stations along the assembly line.

Physical supply chains

The idea of a supply chain is much more intuitive for physical processes (like manufacturing) than digital ones (like software). It's easy to understand that in order to build a wall, you need lumber, fasteners, panelling, and paint; and that those materials need to come from somewhere.

The supply chain for physical materials typically begins with manufacturing, then distribution, wholesale, and retail.

If you need 100 sticks of lumber, you'll purchase them from a retailer, which will reflect in their inventory and cause them to order an extra 100 sticks of lumber from their wholesaler. The wholesaler will then signal to their distributor to add an extra 100 sticks to their monthly order which tells the manufacturer to produce 100 new pieces of lumber.

- Purchase from a retailer

- Retailer orders more from wholesaler

- Wholesaler orders more from distributor

- Distributor signals manufacturer to produce more

That's an efficient supply chain. Only the materials that are required by the end-user move downstream. Since the end-user is the one paying for it, moving inventory they have not paid for increases the expenses for everyone else.

Software supply chains

Software supply chains move data, not inventory, but moving more data than is required by the user creates similar costs and inefficiencies.

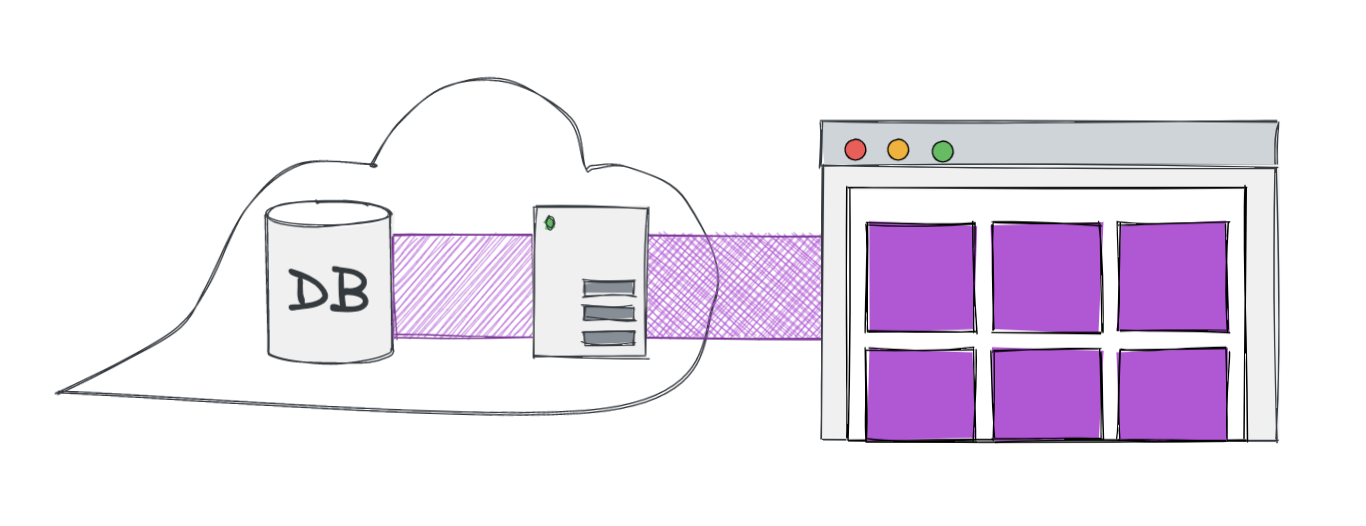

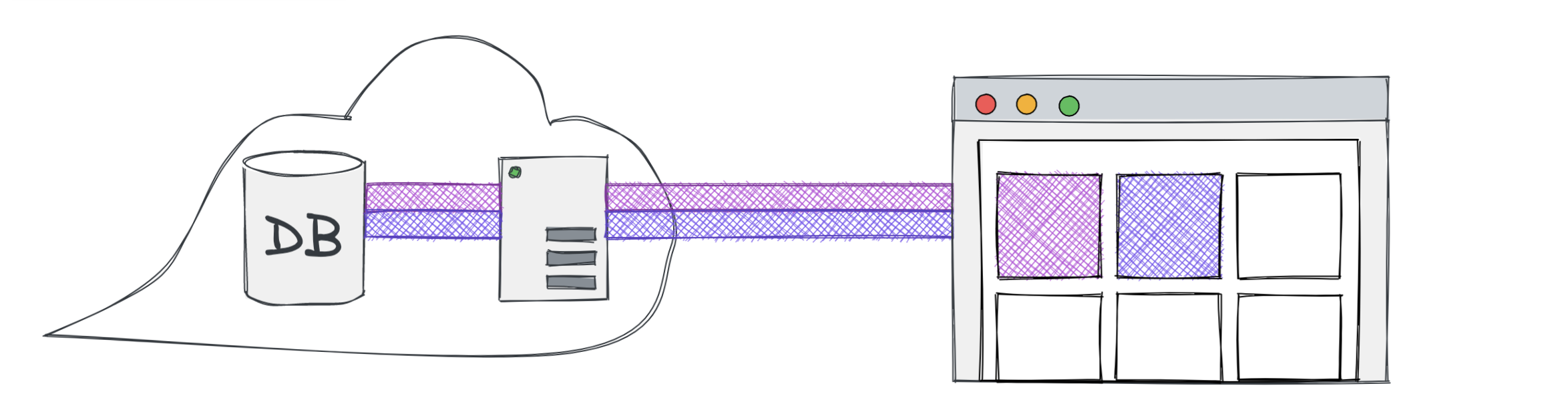

One example of a software supply chain is a process beginning at the database, moving through a server across the internet to a website.

For a user to see a list of products on the page, the page would query a server, which fetches them from a database, and then the products follow the supply chain back to the user.

- Client wants to display list of products

- Client sends request to server

- Server queries database for products

- Database returns list of products

- Server returns products to client

- Client displays products

When we care about web performance, we're talking about optimizing this supply chain so that the round trip is as fast as possible. The throughput of this round trip is far more important than any of the individual efficiencies, but by analyzing the individual steps we can more easily recognize where the bottlenecks may be.

Client-side data

The amount of data you can hold on the client is limited by the amount of RAM the user has. Most of the time this isn't an issue, but exceptional circumstances can cause sites to break on mobile devices. If you're doing data visualizations, pay more attention to this area.

Otherwise, the primary issue with holding data in the client is the cost of getting it there. Transmitting data across the network takes time, and the more data, the slower it will be. Some networks limit the amount of data you can transfer within a time period, especially consumer mobile plans.

It's far too common to see developers overfetching data on the client and filtering down to what they need there. Imagine a situation where you have a database of items, and you're only looking to display those of certain colours.

return mongo .db() .collection("items") .find({}) .toArray()fetch("api/items") .then((response) => response.json()) .then((data) => { return data.items.filter((item) => { if (item.color === "pink") return true if (item.color === "purple") return true return false }) })

On the right side of this image, the browser is displaying pink and purple items, but it also requested data for blue and green items. This is an example of overfetching.

The browser has to wait for all of the data before it can display any of the cards.

Server-side data

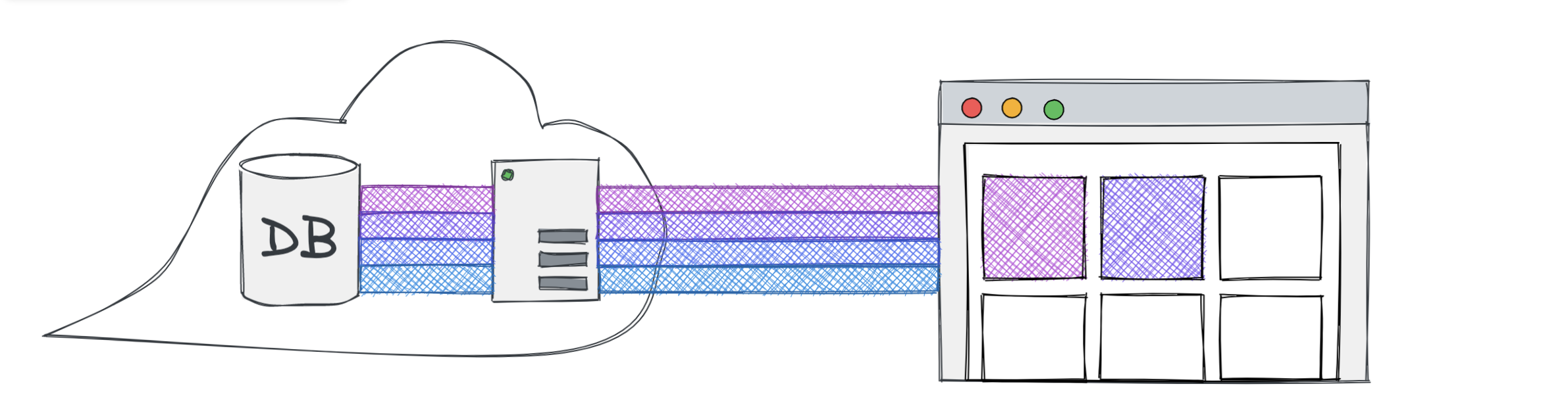

A better approach is to make sure unnecessary data never has to cross the network.

Smaller payloads transfer more quickly, which means the items appear on-screen faster. Handling the filter logic in the backend, in a specific handler meant to present that data, is often easier to manage than any attempt to do so in the front end. That's a secondary bonus, but a significant one.

const items = await mongo .db() .collection("items") .find({}) .toArray()return items.filter((item) => { if (item.color === "pink") return true if (item.color === "purple") return true return false})fetch("api/items") .then((response) => response.json()) .then((data) => data.items)

Now only the data that is needed by the client ever gets returned from the server. That's great, but there's still room for improvement.

Every item is being transferred from the database to the server. This might be a network request across the internet, and therefore subject to the same performance repercussions of overfetching on the client, but servers are often closely coupled to databases in a sort of private network situation (virtual or otherwise). In those situations, data transfer between database and server can be very fast, and is less likely to be the bottleneck in your supply chain.

But servers have limited RAM, and querying a document from a database, moves it directly from database storage (which is cheap and abundant) to server-side RAM (which is expensive and limited).

Imagine if the items collection contained 1 GB of data.

const items = await mongo .db() .collection("items") .find({}) .toArray()return items.filter((item) => { if (item.color === "pink") return true if (item.color === "purple") return true return false})This query, in one line, would instantly allocate 1 GB of RAM on the server in order to hold those items. If that RAM wasn't available, it would either have to wait until it could free the memory from other processes, or fail entirely. In scalable cloud environments, that could trigger the environment to dynamically adjust to a higher (more expensive) product tier.

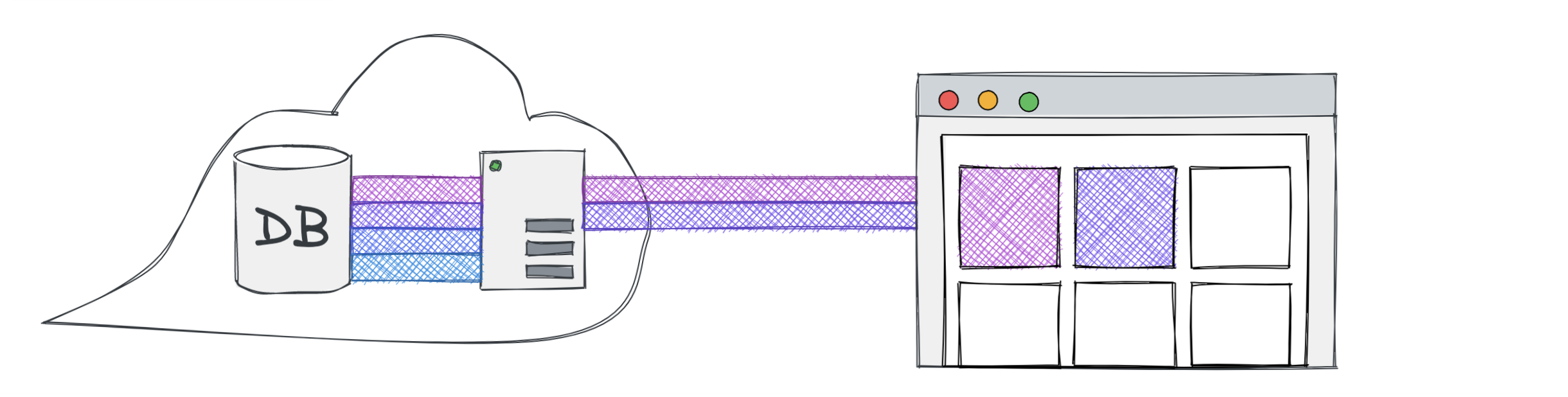

Filtering in the database

const items = await mongo .db() .collection("items") .find({ color: { $in: ["pink", "purple"] }, }) .toArray()return items

By moving the filter logic out of javascript and into the database query, we keep the utilized server RAM to a minimum, and our supply chain no longer has any visible bottlenecks.

Holding data in the database uses storage space. Storage space is cheap, and databases are fast. Some databases are optimized more for frequent reads or for frequent writes which can be a factor here, but for most applications, the database is not the bottleneck.

What next?

We'd have to dive deeper to see more optimization strategies. It may turn out that we don't need every single field on each item. If we know exactly which fields we need up front, we can modify the database query to only return those. Otherwise, there are some query standards like Google Discovery and GraphQL that allow the client to specify which exact fields they want on each request.

It could also turn out that we don't need every item at once. A pagination strategy can cut down on the initial request size dramatically. Instead of fetching hundreds of items, we can fetch only the ones that will be visible on the screen at once.